Grounding the Bible: 10 Old Testament Figures That We Know Existed, With the Evidence That Proves It

Between royal boast-inscriptions, shattered stelae, and clay bullae stamped into wet earth nearly 3,000 years ago, the Bible’s world occasionally snaps into sharp historical focus. This article follows that trail—ten names from the Old Testament that can be checked against the records of Israel’s neighbors, from the Mesha Stele’s “House of Omri” to the Assyrian monuments that place Israelite kings in the shadow of empire, and on to Babylon and Persia where the exile-and-return story intersects with external evidence. Along the way, we’ll separate what archaeology strongly supports from what it only suggests (and what it doesn’t support at all), so the past stays fascinating without turning into wishful thinking.

Is the Bible a historical document?

The short answer is not in the modern sense, but saying that without elaboration can be as misleading as insisting the Bible is literally true from cover to cover.

The Hebrew Bible / Old Testament is an amalgamation of different texts from different periods, written and edited over centuries. Many scholars do associate a major editorial and literary program with the late 7th century BCE (the era of Judah’s King Josiah), especially around Deuteronomy and the “Deuteronomistic History” (broadly, the narrative running from Deuteronomy through Kings). But it is too strong to say “the Bible was composed for the first time” by Josiah. (Josiah’s era matters, but it was not the one-and-only moment the Bible came into being.)

The date(s) of composition matter because many biblical narratives preserve traditions and memories that were later written down, edited, and interpreted. As a rule of thumb: we tend to get firmer historical footing once we enter the period where Israel and Judah intersect with the record-keeping empires around them (especially Assyria, then Babylonia and Persia).

It is also important to note that archaeology is not finished. New finds can sharpen, complicate, or occasionally overturn prior assumptions.

Here is where we are now.

1. Omri: the Earliest Person to be Directly Corroborated

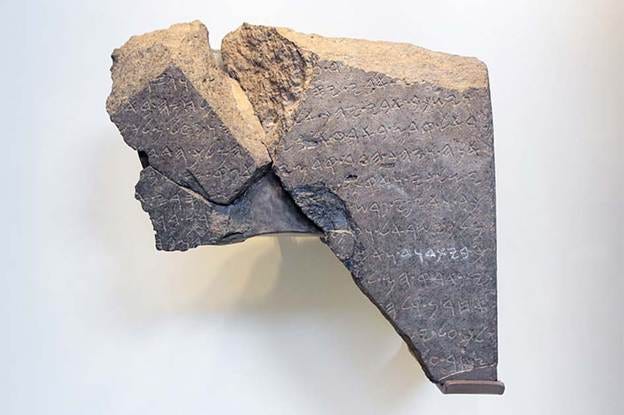

This is the Mesha Stele, from around 840 BC. Mesha was a Moabite king and the stele contains a list of his achievements. However it starts by noting how the Moabites had been sorely pressed by attacks from the Israelite King Omri. Omri is only a passing character in the Bible, but there he is, and now we can say he was a real person.

2. King David: the Earliest Hebrew King to be Mentioned

Firstly, let us be clear: archaeology does not confirm David’s biblical biography or the full scale of his described kingdom.

However, the Tel Dan Stele (9th century BCE) is widely presented as containing the earliest-known extrabiblical reference to the “House of David”—a dynastic label for Judah’s royal line. This does not prove “David as described,” but it is strong evidence that a Davidic dynasty-name was in use within about a century or so of the time David is usually placed.

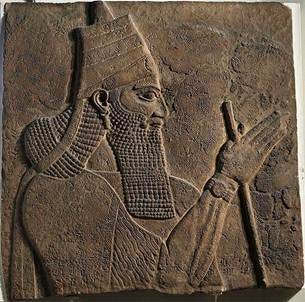

3. Jehu: The First Depiction of a Biblical King

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (Assyria) includes a tribute scene identified with Jehu of Israel (or possibly his representative) submitting and bringing gifts. Either way, it is one of the most famous visual attestations connected with a biblical Israelite king in Near Eastern royal art.

A frequently noted nuance is that the kneeling figure could be an envoy rather than Jehu himself, but the tribute record and identification are standard in discussion.

4. Tiglath‑Pileser III: The First Non‑Hebrew King Who Featured in the Bible (for Assyria, we’re on firmer ground)

Assyrian history is well documented, and Tiglath‑Pileser III is known in great detail from Assyrian sources. He also appears in the biblical books of Kings and Chronicles, making him a classic example of an externally attested ruler who intersects with the biblical narrative.

From this point onward, many events and names in Kings/Chronicles sit in the same historical world as Assyrian royal inscriptions and administrative records—often with differing emphases, but within a shared timeline.

5. Isaiah, the First Character Who Isn’t a King (possible, not definitely known)

A bulla (clay seal impression) from excavations in Jerusalem has been read as “Belonging to Isaiah … nvy.” The excitement comes from the idea that nvy might be the beginning of the Hebrew word for “prophet” (navi). But the bulla is damaged where we would need the final letters for certainty, and “Isaiah/Yesha‘yahu” was not an impossibly rare name.

So this can be described as possible evidence, not a confirmed appearance of the biblical prophet Isaiah in the archaeological record.

6. Esarhaddon and Sennacherib: Palace Intrigue That Overlaps with the Bible

Assyrian succession politics were brutal—and unusually well documented.

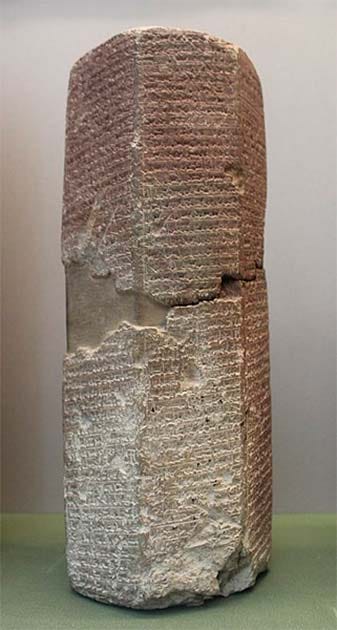

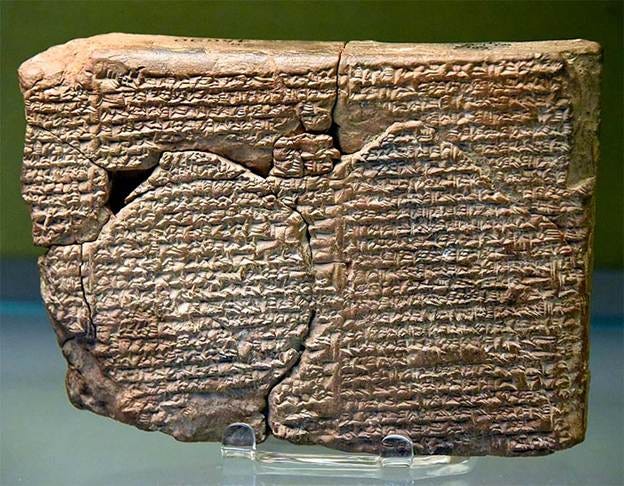

By now in the timeline the kings of Judah and Israel are being corroborated left and right by Assyrian sources, most of which note how the Assyrians are great conquerors and how much tribute they are receiving from said kings. One tablet, known as the Prism of Esarhaddon, contains a little detail regarding the Assyrian succession: Esarhaddon, Tilgath’s great grandson, ascended when one of his brothers killed his father Sennacherib. And the Bible notes this too: it would seem that, by this point at least, they are faithfully recording events

Multiple ancient sources report that Sennacherib was assassinated in a coup involving his own sons, and that Esarhaddon became king afterward. The Bible also reports Sennacherib’s death at the hands of sons and Esarhaddon’s succession (2 Kings 19:37). The basic alignment here is real, even if each tradition frames the story differently.

7. Shoshenq: The First Pharaoh (and why “Jerusalem” is trickier than it sounds)

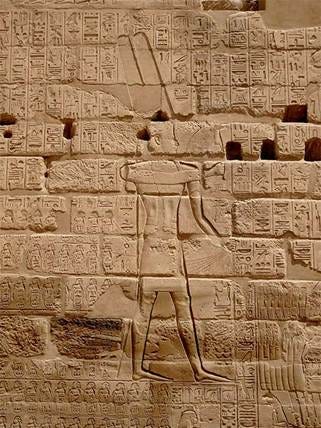

Pharaoh Shoshenq I is very commonly identified with the biblical Shishak. His campaign list is carved on the Bubastite Portal at Karnak.

But one detail should be handled carefully: Jerusalem is not among the surviving place-names on the Bubastite Portal list (even though Jerusalem is central in the biblical account). This does not disprove a campaign that pressured Judah, but it does mean we should avoid saying the portal straightforwardly records “including Jerusalem” as a conquered or listed city.

8. Nebuchadnezzar II: Conqueror of Judah

Nebuchadnezzar II is one of the best-attested monarchs of the ancient Near East. The destruction of Jerusalem and the deportations that form the background to the Babylonian Exile are broadly accepted as historical realities anchored in Babylonian imperial history.

From the perspective of biblical composition, many texts were shaped, compiled, and reinterpreted in the long shadow of exile and return.

9. Belshazzar: Where the Bible’s Storytelling and History Don’t Line Up Cleanly

The problem with corroborating sources is that they will catch you in a lie. And the problem with the compilers of the Bible after the Babylonian Exile is that they weren’t above massaging the truth in search of a compelling narrative (which some might see as an understatement). According to the Bible and to everyone else, the Babylonian Exile ended with the Persians of Cyrus the Great conquering Babylon in the time of Belshazzar, last Babylonian King. The Bible says Belshazzar was the son of Nebuchadnezzar, but other sources like the above tablet all point to him being his great-grandson. Perhaps the Bible wanted to minimize the period of the Babylonian Exile, making it look like the Jews returned to Jerusalem after a decade or so, rather than almost a century

Belshazzar is a real historical figure, but it is important to describe him accurately.

The Bible’s description of Belshazzar as Nebuchadnezzar’s “son” is typically treated as historically problematic (though “father/son” language can sometimes be used loosely in ancient royal contexts). The key point is: this is a place where the biblical narrative does not map neatly onto the best external reconstructions.

10. Cyrus the Great (and what the Cyrus Cylinder does—and does not—say)

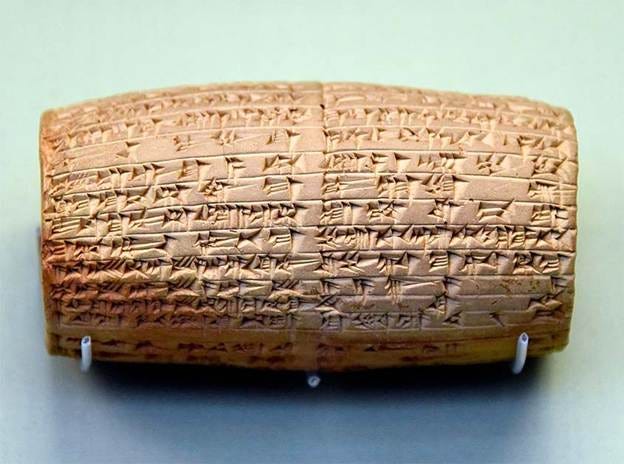

Cyrus the Great is firmly historical, and the Persian Empire did practice policies that included restoring sanctuaries and allowing displaced groups to return—policies that fit the broad idea of a “return from exile.”

If the Bible writers scorn the Babylonians who had conquered and imprisoned them, what did they think of Cyrus the Great, the man who conquered Babylon and set them free? Well, they called him the Messiah. The Decree of Cyrus, speaking of religious tolerance, is recorded in the Old Testament in full on two separate occasions.

However, it is crucial not to overclaim: the Cyrus Cylinder does not mention Jerusalem or the Judeans. So it should not be presented as if it literally contains the biblical “decree” text recorded in Ezra as a direct quotation. Rather, it is best treated as evidence for a general imperial policy environment that makes a Judean return plausible, while the biblical decree texts remain their own literary and archival tradition.

As for “Messiah”: the Hebrew Bible can apply “anointed” language to more than one figure, and Cyrus is famously spoken of in elevated terms in that tradition. Readers should understand that this is not the later, narrower meaning many people associate with “the Messiah,” but it is real biblical language in context.

By Joe Green (updated)

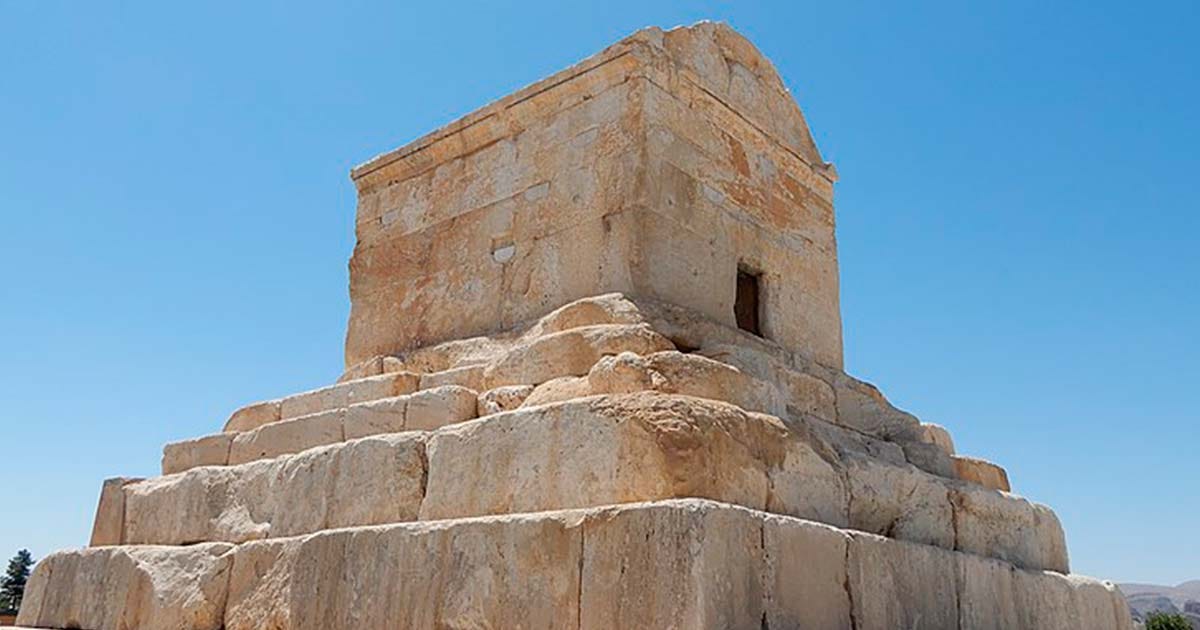

Top Image: The tomb of Cyrus the Great, who freed the Jews from Babylon in the Old Testament and the figure to whom they gave their title “Messiah”. Source: Zythème / Public Domain.

References

UsefulCharts, Youtube, 2023. 37 Bible Characters Found Through Archaeology.

Elayi, J, 1987. Name of Deuteronomy’s Author Found on Seal Ring. Available at: https://cojs.org/name-of-deuteronomys-author-found-on-seal-ring/

Britannica, 2023. Cyrus the Great, king of Persia. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cyrus-the-Great

Tel Dan Stele overview (earliest extrabiblical “House of David” reference). Available at: The Jewish Museum

Black Obelisk (Jehu tribute scene; British Museum object record). Available at: British Museum

Black Obelisk nuance (Jehu vs envoy) Available at: COJS – Annals Edition 4

Mesha Stele (“House of Omri”). Available at: Wikipedia

Isaiah bulla caution (damage prevents certainty) Available at: Biblical Archaeology Society

Shoshenq/Shishak and the missing “Jerusalem” problem on the surviving list. Available at: Biblical Archaeology Society

Cyrus Cylinder does not mention Jerusalem/Judeans. Available at: Biblical Archaeology Society

Belshazzar as crown prince/co‑regent and son of Nabonidus. Available at: Wikipedia

Brilliant dive into how material evidence grounds biblical narratives. The way the gypsum panels and clay bullae work as primary sources rather than just artifacts is exactly what separates solid history from speculation. I always found it fascinating how assyrian administrative records treat Jehu's tribute so matter-of-factly while the biblical text frames it as prophetic fulfillment, same event different framings. Really shows why we need both archeology and textual analysis to get close to what actually happend.

Liminal Joy

By Kathleen Tonn

I sat wrapped in my fleece quilt looking out my apartment window. Snowflakes fell onto the thick blanket of icy snow covering both street and ground beneath my fourth floor efficiency. My apartment building lost power under the weight of the storm surging across the United States. Historic storm with twenty-one states declaring a state of emergency.

I shivered.

The one candle lit inside my room warmed my hands as I left my window seat. Hundreds of thousands like I snowed in, cold and alone.

But was I?

I looked around my apartment now in shadows as I climbed beneath the covers of my bed. I pulled the blankets up to my chin as I turned on my side to look at the glowing Yankee, Christmas candle.

Is the Bible true?

What I know about the Bible could fill an ink cartridge in a pen. Not much.

For most of my life, the Bible meant nothing, and frankly, I held contempt for those Bible thumpers.

Alone in this freezing cold apartment I wondered about the Bible I had disdain for. If I died in this freezing cold apartment, alone and hungry, what would happen to me? A street preacher told me last year that I was going to hell when I told him to shut up.

Is that true? What is hell, and would I go there?

My teeth chattered as the room’s temperature dropped in harmony with the below zero temperature outside.

The candle flame danced about with the draft coming in through the single pane window.

How many days will my apartment be without power? It has already been twenty-four hours.

I opened a can of fruit cocktail and ate that. It tasted awful. Not even the McDonalds five blocks away was open. If it was I would go out in the cold and snow and get me a Big Mac.

My stomach growled. Is there really a God? Is it fantasy? Is it some old peoples’ morbid joke for humanity. Telling us that a God loves us when we suffer so?

The blankets didn’t stop my teeth from chattering. If there was hot water, I’d take a shower to warm up by. But no. No electricity and no hot water.

The flame continued to dance encouraged by the drafty window.

I started to create a song for the flame. I entitled it Liminal Joy. The flame was having more fun than I.

The lyrics had one repeat refrain. “I know more than you do.” That is the only sentence that came to me as I froze beneath my blankets.

Then, to amuse myself I sang those words. I couldn’t help myself. Having a resonant voice, those words bombarded the semi- darkness around me. And the flame danced even more profoundly at those words.

After fifteen minutes of singing those words, I stopped. I just stopped, and the flame stayed still.

It’s glow warmed me in away I can’t quite figure out. I actually felt warm. I took a couple blankets off me. I felt really warm. I wonder why.

Why do I feel so warm?